|

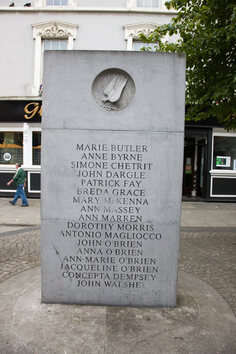

3/19/2021 1 Comment Hate the Bomb/Love the Bomb (Why You should order an Irish slammer instead of a Car Bomb)Any excuse for a party is good by me. Hallmark holiday… Is there drinking involved? I’m in! Holidays that have no relevance to me… Is there drinking involved? I’m in! Celebrating a landmark occasion in another nation’s history, warping it to fit our own cultural ends… Is there drinking involved? Um... I'm cautiously in... St. Paddy’s Day definitely fits in to the latter category. The first St. Patrick’s Day Parade on record was held not in Ireland at all, but in what is now St. Augustine, FL in 1601. In Florida as in Ireland it was a somber religious holiday. That didn’t start changing until the 1970s. I willfully disregard this particular cultural incongruity, as I disregard the incongruousness of celebrating occasions that have no relevance to me, nor any real relevance at all. I like to celebrate, hang out with friends, drink, dance and laugh the night (or day, whenever) away. As long as I don't feel that it's causing cultural damage, I’m OK with it. Where my qualms come into play is with the celebration of a horrific event in another culture. Imagine you’re walking down the street in the Irish city of Dublin. Its nearing 5:30pm. You’ve finished working for the day and are only a block away from your favorite pub, the Welcome Inn. Dublin bus drivers are on strike, so there are a lot of people sharing the sidewalk with you. You notice some of the people near you. There’s a young couple with two infants coming towards you, and an old man who looks like he might be headed to the pub, as well. Across the street you see a teen-aged gas pump attendant waiting for the next car to pull in. You can practically taste your first pint as you reach for the door. Then you hear an explosion! In the same moment you instinctively stop & turn to see “a big ball of flame coming straight at us, like a great nuclear mushroom cloud whooshing up everything in its path.” That last sentence is a quote from a man who survived this very real explosion. The people in this scene are not fictional, they all died in this bombing. It was a car that had exploded, and within 90 minutes of this first attack three other car bombs would go off in or near Dublin, killing 34 people. The date was Friday the 17th of May 1974. Though this car bomb attack was perhaps the worst, it wasn’t the first, and it certainly wasn’t the last. It was one of many that took place during the time of “The Troubles.” The Troubles lasted from the late 1960s – the late 1990s. The conflict was primarily political, between people who wanted Northern Ireland to remain part of Great Britain and people who wanted Northern Ireland to leave and join a United Ireland. There was much violence done by both sides, including such common use of car bombs as weapons that when somebody in the U.S. was looking to name a drink that had all Irish ingredients and involved splashing and bubbling, calling it an Irish Car Bomb seemed pretty clever. But it wasn’t. The name sucks unless you’re into drinking other people’s misery. It is a delicious drink though, (that’s right, this fancy mixolologist said it) and deserves to be enjoyed. So, let’s continue to use St. Patrick's Day as an excuse to drink and abuse green food coloring, but how about we also all agree to adopt an alternate name for this drink, one which has already been gaining traction, the "Irish Slammer". Time for a recipe! Today you get a two for one, both the Irish Slammer, and Homemade Irish Cream. Irish Slammer 1/3 of a pint of Guinness A shot glass half full of Irish Whiskey, half full of Irish Cream Drop the shot glass into the pint. Raise to your lips and chug fast, you want it to curdle in your stomach, not in the glass. DIY Irish Cream 2 oz Irish Whiskey (I like something around 90 prf, like Teeling) 1 oz Simple Syrup or Demerara Syrup* 1 oz Heavy Cream Pinch Cinnamon Dash Chocolate Bitters 4 drops Orange Blossom Water Shake with ice, strain in to a rocks glass. Serve neat or over ice. Or with Coffee. Or Ice Cream. *Turbinado Syrup 2 parts Turbinado or “Raw” sugar 1 part water Combine in a pan over medium high heat. Stir until sugar is dissolved. Selected References: History of St. Patrick's Day https://www.history.com/topics/st-patricks-day/history-of-st-patricks-day Hidden Histories of the Northern Ireland Troubles, a podcaast by Gareth Mulvenna

1 Comment

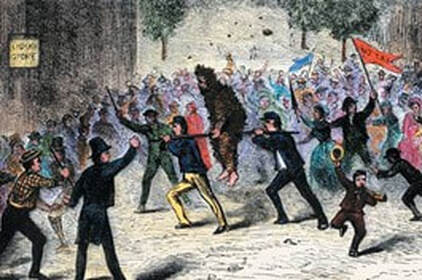

1/21/2021 0 Comments What Happened after the first fourth of July? Alexander Hamilton and the Whiskey Rebellion.On July 4th, 1776, the thirteen colonies had declared their independence from England. Fifteen years had passed since that day, and much had been done. The revolutionaries undertook and won their war for independence, the United States of America was created with the writing and ratification of the constitution, the first President, George Washington, had been elected and inaugurated, and Alexander Hamilton had been appointed as the first Secretary of the Treasury. Now, in the spring of 1791, Hamilton saw his federal excise tax on distilled spirits passed by Congress. This “Whiskey Tax” as it came to be known, was the last step of a financial plan for the country that he had been doggedly working on and lobbying for, and it would be the first tax imposed on the people of the newly formed country. Hamilton and those who supported him saw the plan and its tax as being critical to the growth of the country both internally and internationally. Small farmers and distillers saw it as placing upon them an unfair burden that their businesses might not survive. The “Whiskey Rebellion” was born. Whiskey had become the “spirit” of the new country. As the previously popular rum became harder to get during the revolution (largely due to oceanic trade being interrupted), buying local whiskey made from locally grown grains was not only cheaper (since it avoided the added on cost of import and transport), drinking it also came to be seen as a patriotic act. It was much easier to transport a couple of barrels of whiskey over long distances and through the Appalachian Mountain Range that covered the western part of the country than it was to transport the many bags of grain it took to make the whiskey. This made it the best way for farmers to move and sell their grain crops. People across the country had come not just to produce and buy whiskey for consumption, but also to depend on it as a commodity, essentially using it as currency. This was important, because in the more distant parts of the country there wasn’t a lot of money in existence, either in the form of the (basically collapsed) “continental” paper, or hard coins. By taxing spirit production, an encumbrance was being placed on a significant part of the economy of the frontier areas of the U.S. One of the ideas inherent to Hamilton’s plan was that the powerful and the wealthy were the people most likely to help the country grow. Toward that end a goal of the tax was to shift alcohol production away from small business and toward industrialized distilleries (this was the goal for the economy in general). There were two separate standards for carrying out collection of the tax, one for more rural, hard to get to areas (small farmers and distillers) and one for more urban (industrialized) areas. Justified because they were harder to get to and therefore monitor, in the rural areas the tax was figured based on the potential production of a still over the course of a year. Whereas in the urban areas, where monitoring by tax men was easy, the actual output of the distillery was taxed. Since in actuality the small-time farmers and distillers only used their stills for at most a few months out of the year, they came no-where close to producing the amount of alcohol they were being taxed on. In effect, they were paying a much higher tax on their product than the big distilleries were. And if the taxes couldn’t be paid? Land, stills, and whiskey would be confiscated, in effect robbing them of their livelihood and some of their freedom by forcing them to then go work for other people, or even to work in industrialized distilleries and other factories in order to survive. It was not just paying the tax that the people were resisting, it was this perceived unfairness and fear of loss of freedom, among other complexities, that they were standing up against. The Rebellion started in Pitt County, Pennsylvania, near where the city of Pittsburgh was forming. This was then the heart of American whiskey production; it was also part of the western frontier. Along with the western sides of New York, Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia, it was being carved out of the woods (and away from the native peoples) to make room for the farms and towns of the growing country. It was in this far off part of the U.S. that those who were subject to the new tax began their protest through political action, tax dodging, and outright refusal to pay. When these peaceful methods of protest resulted in little change; violence broke out and spread across the region and into Virginia. The angry farmers and distillers would gather, sometimes without but often with faces blackened or otherwise painted, wearing costumes such as women’s dresses and bonnets, or the breeches and feathers of native raiding parties. In such odd and frightening attire, they kidnapped and then tarred and feathered men who were trying to gather the new tax and even neighbors who were complying with it. They broke into and trashed homes where tax offices were located. Their violence and intimidation continued over the course of three years. Their numbers grew to include not just farmers and distillers but also people who owned no land or stills but had been suffering economically during what was the country’s first recession. They effectively took over their local militias and governance, terrorizing anyone who wasn’t with them. The rebellion came to a climax in the Autumn of 1794, when groups as large as 7,000 rebels were meeting and threatening to march on and loot Pittsburgh, to attack local Fort Fayette, and to declare themselves independent of the federal government. At Secretary Hamilton’s urging, President Washington led 13,000 troops through the mountains and into the Pittsburgh area to squash these large gatherings of protesters. This was the first time the U.S. deployed a sizable federalized military force; it was also the first time the United States used the military against its own citizens. The rebels were vastly outnumbered and so they ran. Leaders of the rebellion, frightened for their safety, disappeared into the wild west and Spanish south. Many more of the rebels went into hiding in the mountains. A few were captured, and of those most were acquitted. The two who were sentenced to hang were pardoned. The rebel’s fight was over, the whiskey tax was still in place. What would our rebels have been drinking? The whiskey they made of course! Something as bold and high octane as they themselves were, Monongahela Rye. The regional style had picked up the name from the valley it was made in and the river whose water was often used to produce it. It was distinctive rye whiskey, different from those we’re used to today. Famous for being deep red in color, high in alcohol, and full of rich flavor, it was made using mostly rye grain, with some malted barley. It was distilled using a three column still, a style that is no longer in use today. It would have been common practice to mix that rye into a punch, the extremely popular precursor to the modern American Cocktail that would become all the rage in the following century. It’s reasonable to assume, in fact, that many bowls of rye punch were drained during early American celebrations of the Fourth of July. American Whiskey Punch (Recipe taken from “Punch: The Delights and Dangers of the Flowing Bowl” by David Wondrich.) Making a good punch often requires just a bit of advanced work. Ice: It’s ideal to have one big piece of ice. This can be accomplished by freezing water in a Tupperware container that fits inside your punch bowl. Oleo-Saccharum: This is sugar that is aromatic with citrus oil and is the key to making this punch. To make it mix the peels of two lemons in 1 cup of sugar and let sit for an hour. In your punch bowl mix the following: All 8 oz of the oleo-saccharum 6 oz of lemon juice 1 cup of water stir until the sugar is dissolved, then add: 12 oz of rye whiskey. The higher the proof and the higher the rye content the better. 3 cups of water stir it all together then carefully add your big block of ice. Serve your friends and yourself and raise a toast to the U.S.A. on its birthday. Have a great Independence Day! Please drink and celebrate responsibly. References: Hogeland, William. The Whiskey Rebellion: George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and the Frontier Rebels Who Challenged America’s Newfound Sovereignty. Simon & Schuster. E-book. 2006. Degroff, Dale; Frost, Doug; Olson, Steven; Pacault, F. Paul; Seymour, Andy; Wondrich, David. The BAR Manual, Version 8.1. Beverage Alcohol Resource. 2019. Hamilton: The Musical Animatic Version. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MwqkmfFJ6LU. Spoelman, Colin and Haskell, David. The Kings County Distillery Guide to Urban Moonshining: How to Make and Drink Whiskey. Abrams. New York. 2013. Veach, Michael R. Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey: An American Heritage. The University Press of Kentucky. Kentucky. 2013. Wondrich, David. Punch: The Delights (and Dangers) of the Flowing Bowl. The Penguin Group. New York. 2010. Phillips, Matt. The Long Story of U.S. Debt, From 1790 to 2011, in 1 Little Chart. Theatlantic.com. November 12, 2012. Szramiak, John. The History of Money: A Brief Look at American Currency. Businessinsider.com. June 18, 2016. Townrow, Stephanie Krom. The Whiskey Rebellion: An Interactive Mapping Project. http://maptherebellion.com/. New York University. 2015. Grun, Bernard. The Timetables of History: A Horizontal Linkage of People and Events. Touchstone Edition. Simon and Schuster. New York. 1982. |

by Sarah L.M. Mengoni

ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed